An essential skill in today’s world

This isn’t exactly the Information Age we were promised. Instead of a bottomless well of the wisdom of the ages, we find ourselves wading through a swamp of misinformation and ignorance. Maybe we should be calling it the Misinformation Age.

In the Misinformation Age, distinguishing between fact and fiction is an essential skill. We should teach fact-checking in schools. For all the talk about “fake news,” very little guidance on how to sift through what we are reading and hearing is available. In the Misinformation Age, we have to take it upon ourselves to check the info we are consuming.

The information we circulate decides elections. It destroys relationships. It ends friendships. Family members become estranged. We just cannot afford to be flippant about it anymore.

TL;DR Main points, which I will expand on below:

- Be humble enough to know that your first impulse to believe or disbelieve something will not always be right. Your impulse of whose authority to rely upon will not always be right.

- Before the fact-checking can begin, you need to be honest with yourself and recognize your own biases. Our brains are wired to be clan-based. The more someone is like us, the more likely we are to assume that what they say is true.

- Confirmation bias is your single greatest enemy. Confirmation bias is when our brains automatically ignore any new information that contradicts what we already believed and hold on like a vise to whatever new information reinforces what we believe. If a statement reinforces your worldview you need to question it just as much as – if not more than – if it doesn’t reinforce your worldview. Confirmation bias is in our DNA. That’s why this is so hard. We have to fight against the way our brains have evolved in order to truly have a claim on a factual understanding of anything at all.

- Related, the more emotional something makes you, the more you need to question it. If you become angry at someone or a group of people based upon some information you receive, you better be damn sure that information is accurate before you hold on to a grudge.

- Distinguish between statements of opinion and claims of fact. “The moon is made of cheese. Hey, agree to disagree. That’s just my opinion.” Nope. That is a claim of fact for which you need proof or a reliable source.

- Take responsibility for the claims of fact that you make. When you spread misinformation on social media, you are responsible for anyone downstream from you that is now misinformed. In the modern world, we cannot take the transmission of information lightly.

- First step in fact-checking: Google (or whichever search engine you prefer). So much misinformation can be dispelled by a simple Google search. Do not post a claim of fact if you are just regurgitating it from somewhere else without at the very least Googling it. A lot of “facts” you won’t find anywhere outside of meme form. For the love of all that is good and true, please do not post these things.

- It’s not about Google. If you don’t trust it, try another search engine. Google just provides sources for you to sift through. If you don’t like the first results, first check yourself to make sure you’re not experiencing confirmation bias (i.e. you’re not trusting it just because it’s not saying what you want it to say), and then keep digging.

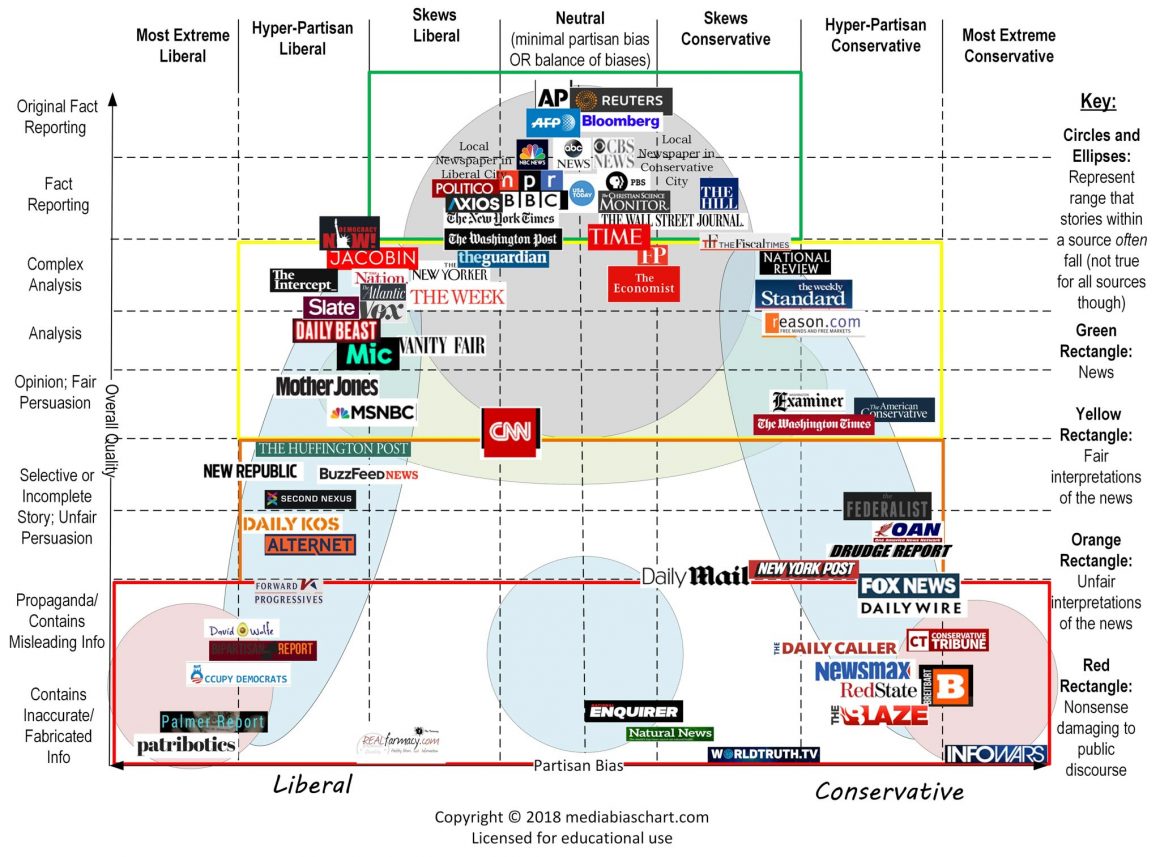

- If Google turns up other sources making the same claim, the next step is to assess the sources. Most of the time, claims of fact on the Internet will come from a news source. This is not optimal, but it is what it is. If you are relying solely upon a news outlet’s statements of fact, be very discerning. Keep in mind the bias of that outlet. Not just the ones you perceive to be biased in the opposite direction of your bias. Question the sources that lean the way you do just as much (confirmation bias again!). There is a handy chart below that maps out a general idea of how different media outlets lean and the professional rigor with which they work.

- The next step in fact-checking is to find more sources that say the same thing, or sources that contradict it. You can then assess which of those sources is the most reliable. Maybe they’re both the same level of reliable. Then the thing that you’re researching is not an established fact and you cannot claim that it is.

- The holy grail for any scientific claims that might be thrown out is peer-reviewed, academic research. If an article online speaks of any scientific claim of fact, they should have some indication of where they got that information from – or they’re not a source you should be using.

- Become comfortable with ambiguity. Sometimes your fact-checking won’t come up with a clear and certain answer. And it’s okay to admit when that happens. But don’t then repeat the statement you’re not sure about as fact.

- Sometimes it just comes down to what “feels right” to an individual. In some contexts, that’s okay. Just be honest about it. Don’t say it like it’s an absolute truth.

- Normalize changing our minds and adapting to new information. Normalize admitting that we don’t know. Become comfortable citing sources as often as possible in everyday life. Normalize saying things like “According to…” in casual conversation and social media.

- For Pete’s sake, take it seriously!

Humility

The first step is being humble enough to realize that your first thought or impression is not going to be right much of the time. A lot of research on political psychology shows that our brains are just not wired for thinking objectively about every claim of fact that we receive. (I’m getting some of this from this book, but there’s a broad range of research that has come to the same conclusions.)

We rely to a large degree on the authority of the person or people giving us the information. We get an impression in our heads that this person or that media outlet is trustworthy and then that’s that. If that person speaks, you are going to believe what they say the vast majority of the time.

And a lot of the time, that’s fine. Parents tell a child that it’s unacceptable to lie, steal, and cheat, and the child believes them and acts accordingly. Your teacher tells you that Japan exists and that two and two make four, and you believe her or him. Our brains being wired that way makes sense.

But no one was really telling you that stealing was okay and that Japan doesn’t exist (hopefully). So what happens when you have two contradicting claims? Well, the first thing to know is that our brains are wired to be clan-based. For example, the single greatest predictor of your political affiliation is not your economic status, education, gender, or race. The single greatest predictor of your political affiliation is the political affiliation of your parents. (This book again.)

Obviously, many people form different opinions than their parents eventually, but it is our default mode to trust our clan, and the family is the base unit of our clan. From there, our clan can widen out to include those around us. Our extended family, our church, the people at school, the people in our town or city. From there we can widen out to any other type of identity we might have. (Of course, political identity is one of the strongest ones out there these days.) These are the people we expect to give us accurate information. The people we perceive to be like us are always going to be assumed to be more trustworthy sources of information than those who are not like us. That’s just the way we’re wired.

So if you have someone that you perceive to be like you and who speaks definitively – like they have all the answers – you’re probably going to believe him or her.

Beating Our Wiring

So we have to be aware of our wiring in order to think our way around it. That person who is like us and talks like he or she has all the answers is not always going to, in fact, have all the answers. We need to be able to think critically about the information we are receiving even if we like who it’s coming from.

You like your Uncle Frank. He’s a nice guy, he’s a good dad to your cousins, and he’s really great at his accounting job. That does not mean that his every Facebook pontification should be taken as gospel. This may sound obvious, but we don’t think about it when it’s happening.

One of the most important lessons we can learn is just to be aware of the situations in which we are taking things as fact when we have no real reason to.

It takes conscious effort. It’s hard and, honestly, intellectually exhausting to constantly be checking ourselves for every single thing we believe.

Opinions vs. Facts

Opinions are subjective statements. You can state them as a fact without it being disingenuous. For example, if I said, “‘The Room’ is the best film ever made,” you wouldn’t think that I was trying to state this as an absolute truth. We all know statements of preference like this are opinion. A person doesn’t need to cite a source for their dubious taste in movies.

Claims of fact are objective. They are either true or they are not. It should be possible to fact-check them. We should have some way to prove these statements, or else how can we say that they are objective truth? How can you know that thing is true if a reliable source didn’t tell you about it, or if you didn’t somehow prove it yourself?

Opinions:

- “The government has gotten too big.”

- “Guns should be outlawed.”

Someone might ask you what you mean by that or why you feel that way, but you don’t need to prove those statements. They are your opinion, and that’s fine.

Claims of fact:

- “10% of all immigrants are criminals.”

- “Most gun deaths are caused by white people.”

You better be able to prove those last two statements if you’re going to say them out loud or online. And if you hear someone else say things like that, your first thought should be, “Where did they get that from?”

Suppositions are trickier. For example, when Syrian refugees began pouring into Europe around 2015, some Europeans supposed that some radical Islamic terrorists were sneaking in with the masses. Now this is a claim of fact, and it’s theoretically one that could be proved or disproved at some point. But at that moment there was no way to prove it or disprove it. The problem here would not be making statements you can’t fact-check. The problem would be stating them as if they were fact and not being honest about not knowing those things for certain. It’s okay to make suppositions; it’s not okay to act like they are absolute truth.

Of course, some suppositions are vague enough to be unhelpful. “You know, a lot of immigrants are criminals.” This statement supposes something that in a way could be proved or disproved, except that it’s too vague. How many is “a lot”? Yes, of course, some portion of any population is going to be criminal. The statement is implying that immigrants are to be feared, which is an opinion. Is it implying that a higher proportion of immigrants are criminals than the rest of society? Because that’s definitely a claim of fact that we could prove or disprove. A vague supposition like that is sneaking an opinion in under the guise of a provable statement.

Fact-checking Sources

“But Jeremy, none of these sources can be trusted. All news is fake news, and scientists lie about everything.” Well, then you are living in a post-modern world devoid of objective truth where no statement of fact can ever be made.

Let’s say you post something saying “The moon is made of cheese.” I respond with a couple sources that say that is not true. You say, “All sources of information are unreliable.” That does not then default to your statement of moon cheese being true. Because you believe I cannot prove your statement false does not mean that you are proving it true. You’re saying that nothing can be presented as a fact ever, including your own statements.

If you think all sources are 100% unreliable, chances are you’re experiencing confirmation bias because they’re not saying what you want them to say. Journalists do not get into journalism with the ambition of fooling all of society. Scientists do not go into their fields in order to mislead people. They are generally well-intentioned, though of course flawed, human beings.

For the rest of us:

News Sources

As stated above, much of what we consider to be objective truth is based upon various news sources. This isn’t ideal, but it’s the world we live in. The idea is to find reputable sources.

No, this chart is not absolute truth. The two that are most controversial here will be CNN and Fox News. If you don’t agree with where those two are placed, that’s fine; the rest is still a pretty good layout. If you want to see why various outlets are placed where they are, you can read about their methodology on their website. Frankly, it’s not very scientific but it also doesn’t really claim to be. I will say that it aligns pretty closely with my experience of these sources. Do not try to prove something to me with Occupy Democrats or Breitbart.

Something else to note about the chart: there is a very important difference between sources that lean one way or the other and those that care about journalism or don’t. The New York Times and the Wall Street Journal may have some bias – and it’s important to know that – but it’s unlikely that either of those sources will just make things up out of thin air. The thing you need to be more conscious of in cases such as these is the choice of which information they present and how it is presented.

If you are unfamiliar with a particular news outlet, you can Google “news source X reviews” and you should get some useful information. You should be able to get a feel for any bias that source might have and if it generally has a good reputation or not.

Scientific/Academic Sources

For scientific claims, the person reporting needs to say where they got their information. Most reporters do not have scientific training sufficient to make scientific claims.

Most of the time, that just means quoting an expert they’ve interviewed. The problem with that is that you can find some scientist somewhere who will say just about anything. “Joe Blow, a PhD from University X, has found evidence that the moon is, in fact, made of cheese, but the scientific community is suppressing his findings.”

Concerned about an expert’s credibility? Give them a Google and see what their credentials and reputation are. If you don’t turn up any research they’ve ever done, that’s a red flag. Did you find there are a bunch of other scientists lining up to talk about how their methodology is flawed and findings are unreliable? That’s more than a red flag. If you ignore all red flags about an “expert” because they are saying what you believe, you are experiencing confirmation bias. It’s your choice it you want believe it anyway, but don’t repeat it as established fact.

More ideally, it would be great if a reporter cites a specific piece of research that can be double-checked. Get comfortable using JSTOR (jstor.org), which is a giant repository of scientific publications. Google Scholar can be a good resource as well. If you’re able to find the actual research, you may not be able to read the whole thing because it’s behind a paywall. But some information is generally on the journal listing, at least enough to know if the article citing that research is citing it accurately.

Peer-reviewed academic research generally goes through a pretty intensive vetting process. Other experts in the same field look over how the researcher/researchers conducted their research and how they interpreted the results. It’s common for a journal to send an article back for revisions, sometimes multiple times, before they will publish it. No, this does not make it infallible, but it’s a good way to establish the credibility of a particular scientific statement.

Other Fact-checkers and Wikis

Yes, Snopes is useful. No, it is not the arbiter of all truth. What’s great about Snopes and Wikipedia and other sites that serve as aggregators of information is that they provide links to their own sources. They can be a great kicking-off point. Follow their links to their sources and then follow those sources to their sources. If you really want to become confident in the information you’re getting, you need to get comfortable following the source rabbit hole, assessing the reliability of each layer as you go. It’s hard. It takes time.

Polls

News outlets are obsessed with polls. They interrupt their regular schedules for “Breaking News” about a new poll coming out. I think we’re all aware of the limited usefulness of polls at this point, but they can still provide some useful information. Fact-checking polling data is usually pretty simple. You just have to verify on the polling agency’s website, like pewresearch.org. It’s important to note the margin of error. You can check to see how many people were asked the questions and how the questions were worded. Just generally, keep in mind the limits of polling.

Ambiguity

Our brains crave absolute certainty. Humans want everything to be put in a nice little box and set aside so that we can move forward. That’s the allure of cults and fundamentalist religion. Someone says they know the absolute truth about everything, and we want so badly to think that’s possible we end up believing crazy things. Like, say, the moon is made of cheese. But even if you subscribe to these belief systems, not every issue has been settled within them. I don’t think a ton of religions have come down firmly on one side or the other on the moon-cheese theory I’ve mentioned a number of times now.

A lot of questions do not have clear answers that we can state with absolute certainty. And yet we state them that way anyway. We all pretend to know things we don’t. We just need to be more honest with ourselves and others about it. Be upfront when you’re just making a supposition. Tell your friend that what you just said is something you read somewhere, and then try to find the source and the two of you together can decide if it’s reliable information.

Be not sure sometimes. Change your mind sometimes. It’s not a competition. No one gets a prize for not backing down from the thing they said at the beginning of the conversation.

Conclusion

If you are interested in a case study in what I’ve talked about here, I created one for you here.

We just don’t have the luxury of not taking fact-checking seriously. The stakes are too high. In the Misinformation Age we have to put in some work to make sure that we – and our friends and families – don’t come out thinking the moon is made of cheese.